The problems with personnel at these ports on the Texas-Mexico border continued into the staff of inspectors as well. Foremostly, ports of entry were regulated by Supervising Inspectors who reported to the Department of Immigration and ultimately the Secretary of Labor, these Supervising inspectors were responsible for the oversight of everyone under them. However, medical inspectors reported instead to the Department of Public Health and ultimately the Surgeon-General, meaning that they were in a different chain of command, further complicating everyday structure. Because these inspectors worked for the Department of Public Health, they were seen as protecting the public of the US from the illnesses of immigrants that could be brought over from Mexico.[1]

Additionally, medical inspectors were often not solely employed by the immigration office and often held other positions at local hospitals and clinics. This meant that they were not always available to the immigration officials everyday and when they were present, often had to get through many inspections very quickly

Discrepancies in hierarchy also led to these inspectors being fairly mobile, as they were controlled by an office in DC and not under local authority. They could frequently be moved around when there were shortages or if a smaller port had a large influx of immigrants.

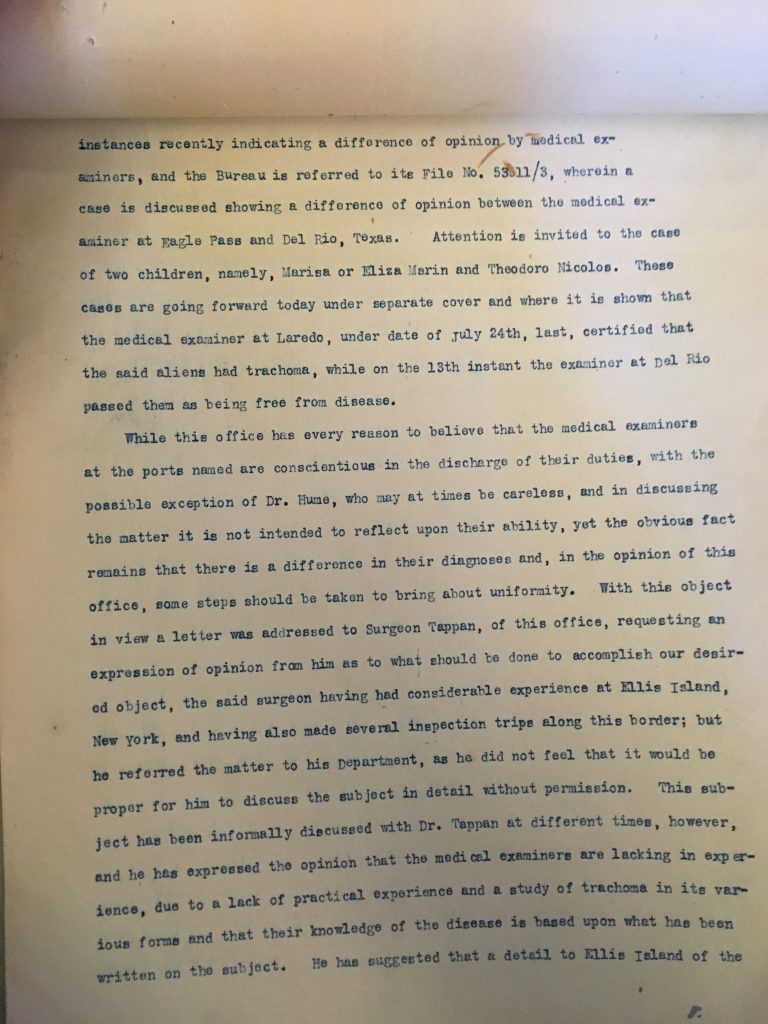

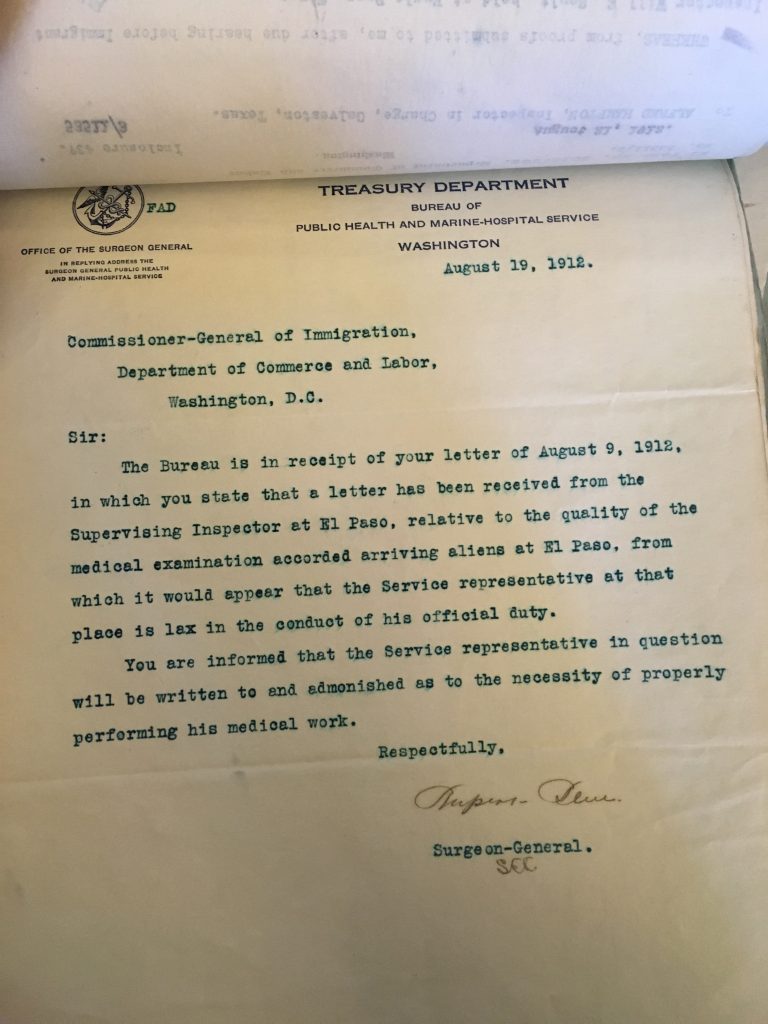

Hierarchy complications also led to differences in the treatment of inspectors as well. For example, Dr. Lea Hume, of Eagle Pass, claimed immigrants to be afflicted with Trachoma when they were, in fact healthy, causing them to be excluded[2]. This got reported to the surgeon general, but aside from a sternly worded letter and a period of probation, nothing ever came of it and Hume held his position at Eagle Pass until his death in 1939.

Meanwhile, Dr. Frederick Wright, from Arizona, falsely gave clean bills of health and was promptly fired from his inspecting position, though he was still able to practice medicine at a local clinic[3]. Wright may have actually been doing this as a means of providing additional labor to the Arizona Mining Company, but a great difference between the handling of his case and the handling of Hume’s is notable. Of course, Hume’s negligence in his duty was seen as more acceptable as he allowed fewer potential immigrants into the country.

[1] File 55,630-025 accession E9, Subject Correspondence, 1906-1932, Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, RG 85 (National Archives, Washington, DC)

[2] File 53,511-003,, accession E9, Subject Correspondence, 1906-1932, Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, RG 85 (National Archives, Washington, DC)

[3] File 53,431-025, accession E9, Subject Correspondence, 1906-1932, Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, RG 85 (National Archives, Washington, DC)