The term habeas corpus directly translates from medieval Latin to “we, a court, command” and is a writ of right that a person can file in the case of perceived unlawful detainment. It entitles those detained to their day in court to investigate whether the detainment of said individual was justified, or not.

In regard to our research, writs of habeas corpus were commonly filed by detained Chinese immigrants held upon Angel Island as they were initially denied entry to the United States. While the reason for the numerous cases of denied entry are numerous (as will be explored later in this blog), the number of habeas corpus writs that were filed before and during our period of research were also large in quantity.

The period in which we see this great increase of habeas corpus cases being heard in court is due to the mass immigration of Chinese into the United States via San Francisco during the late 18th century. Beginning in 1883, the court rooms of some judges, such as Ogden Hoffman, became referred to in the local press as “the habeas corpus mill”. Hoffman was not the only judge that was inundated with cases of this type as other high-ranking judges such as “Lorenzo Sawyer, the state’s presiding circuit judge, played prominent roles in habeas corpus litigation”. The sheer amount of these cases caused problems for the state of California as between the years of 1882 and 1890, Hoffman’s court heard over seven thousand habeas corpus cases. Not leaving much time “to conduct ordinary judicial business”.

The overwhelming majority of the cases we came across during our excursions to the National Archives were heard and investigated as a writ of habeas corpus was filed by the excluded party.

Timeline of Events

The Questioning Process

The interview process was a standard part of the immigration procedure. The initial interview for immigrants when they first entered through Angel Island followed standard immigration interview procedure where they were just trying to figure out information about the immigrant and see if there were any fallacies in their stories.

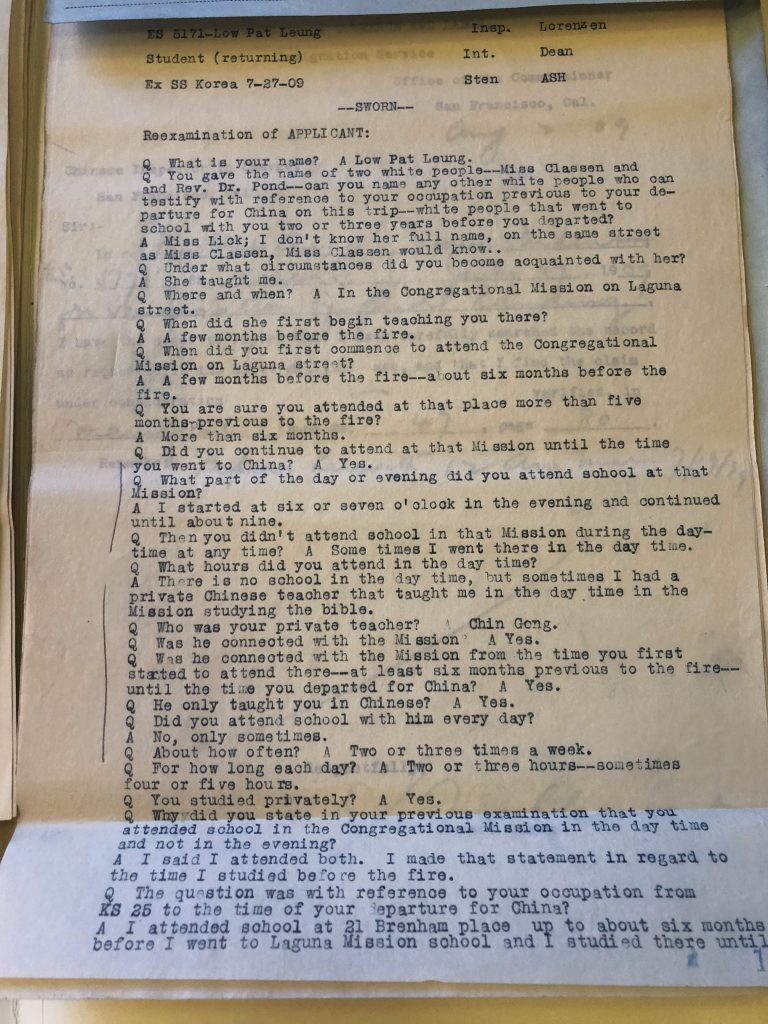

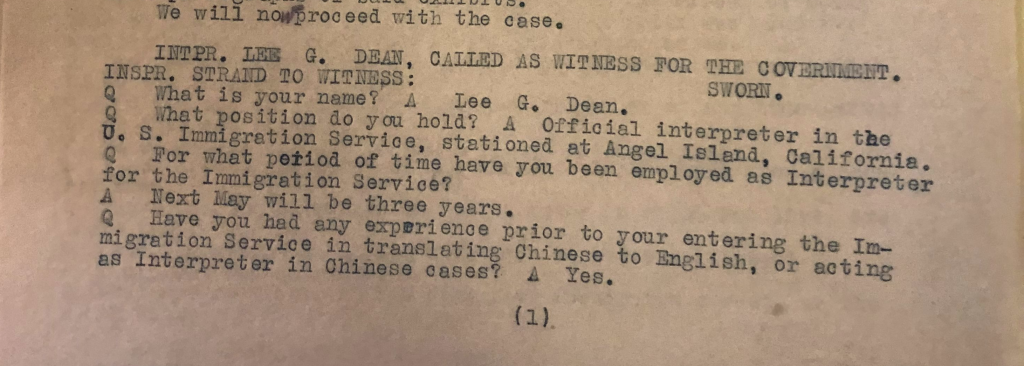

In habeas corpus cases, the goal of the interviewer was to create a case for the prosecution to use in court to make sure the original ruling of deportation was upheld by the judge. The interviewer would often go in with more specific questions as a way of tripping the applicant or one of their advocates up and make sure they had the most accurate version of the truth possible. Habeas corpus questioning was drastically longer than entry questioning where the transcribed pages of the questioning process could range from five transcribed pages to thirty or more pages.

The interviews of the advocates were important to the questioning process since oftentimes the white advocates’ perspective was the one that was most commonly listened too. If an advocate was white, they frequently had shorter interviews than Chinese advocates. A majority of the questions these white advocates were asked were about how “Americanized” these Chinese applicants were if they were claiming to have a previous residency in America. They would be asked questions like if the applicant spoke English fluently or asked about what local shops that they knew the applicant would go to.

Works Referenced

Fritz, Chrstian G., “A Nineteenth Century ‘Habeas Corpus Mill’: The Chinese before the Federal Courts in California” 32, no. 4 (October 1988).

Lee, Erika, and Judy Yung. Angel Island: Immigrant Gateway to America. New York: Oxford Univ. Press, 2012.

Pages:

| What is Habeas Corpus? | Angel Island | Paper Sons | Prostitution and Women | Conclusion |